Reading Between the Text Boxes by Yvette Green

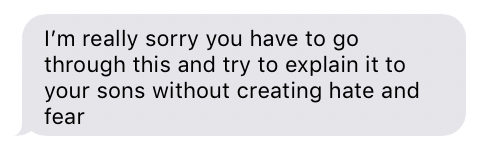

Early on a Saturday morning, a few days after George Floyd was killed and the streets responded in pain, I received this text message from a well-meaning white friend.

He neglected a period where he should have shut up: after “I’m sorry.” He presumed to know what I was feeling or thinking. And if I wasn’t thinking “how do I explain this without creating hate and fear,” the implication was those were the thoughts I should be having.

This first misstep was to issue an apology insinuating that I should be feeling or thinking the way he did. We’d had a conversation a year prior about compassionate listening. In this current instance, I hadn’t reached out. I didn’t ask him to lend me his ear. He was not my countryman in these excruciating moments of vile racism and black rage. In this moment, he was the other and he had an obligation to handle this moment with care or not at all. He sought an opportunity to speak, I did not seek to be heard. Our original conversation about compassionate listening was for his edification, not to further strengthen our relationship. I had decided to do my best to keep him on as a friend or warm acquaintance because he meant no harm.

A year prior, I broke up with a guy I was seeing. Even though it was my choice, I was a bit sad. My feelings were hurt and I was convinced love would ever be evasive in spite of what a gift I was. As I shared my feelings about this new loss and my lack, this white friend responded, “when you’re ready for it, you will have love.” I kindly told him: let’s stop texting right now. I failed to say that is the dumbest, cruelest shit. How is anyone not ready for love? What is the standard for being ready? And who says something like that--you don’t have love because you’re not ready for it-- while someone is freshly wounded. He continued to text me despite my request for him to shut up because the conversation had now become about him, his thoughts on the subject, and what he needed to say. I forgave, sent him something about compassionate listening and slowly backed away from this friendship. Two missteps characterized this exchange. First, an imposition of his thinking as the right way of thinking; and, second, a refusal to hear me when I said, I’m upset, please stop. His need to speak was most important and therefore this relationship would hang in a power imbalance that I refused to negotiate.

In this present moment, a white man’s decision to initiate interaction with the black mother of two black boys after (and regarding) the death of black man by a white system should be handled with care, if at all. Maybe the apology was an attempt to make himself less white. To step forward, unprovoked, and say “I’m sorry you have to explain this to your sons without creating hate and fear,” is a white masculine patriarchal act.

You do not know what I have to do. You do not know what I want to do. And you do not know how I feel or how I think. This is about you. And this white male space you are privileged to occupy and speak from with a degree of authoritativeness. This is part of the problem. This is part of the system that is oppressive.

It was as though he were saying it was my job to combat American voices and pain and fear and hatred. America created the need for us to take to the streets again and again and again. America did this. There was nothing for me to explain. My children can see clearly what this country is and what this country thinks of them by how it treats its’ black citizens. And they are afraid and I am afraid and there is nothing to explain.

But I tried to be kind. I chose my words carefully, specifically for him. I knew he meant no harm, despite how I felt about this message, this apology I didn’t need. I responded via text as gracefully as Natasha Tretheway did to those who failed to understand her grief and offered up lazy language when she needed silence in “Imperatives for Carrying on in the Aftermath.”

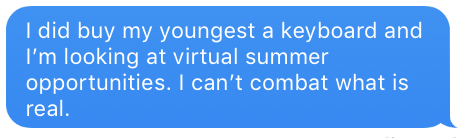

My black sons are marked and you have no idea what that feels like. The fear knots in my shoulders and streams from tear ducts. The anger threatens my sense of self. My own lack of power to protect my black sons is debilitating. But to extend grace further to him, I added:

And I sent him a video of this child’s early attempts at playing “Ode to Joy”. Because this was me being kind and talking about what I would do for my sons. This was me refusing to engage in a conversation where it was my responsibility to change how my children viewed a country that would never be post-racial, that strengthened cops to kill black people with ease. Because I needed to redirect the conversation to commonalities, we build our children up. But the conversation was his:

Had I not been unclear prior, I was uber clear now. This is not about me, a black mother of black boys, this is about a white man in the comfort of his white space gazing on the story of our country personified in cities as people scream to be heard. I lost my grace and stopped conversing. I didn’t breathe; I tensed up and I grew angrier. I had wasted my precious energy on this exchange.

A few days later, as I tried to articulate the weight of the exchange, a girlfriend of mine asked “I don’t understand. Why did you care so much? Were you in (or ever in) a romantic relationship?”

“No. Why did you ask? Why did that matter?”

She said “men and women don’t generally have those kinds of friendships.”

Trying to explain one thing, I had to explain another. I cared because I had let him in and I trusted him and now it was time to let him out. There was nowhere else to go. And I didn’t want to bite my tongue or share my secrets or count on him. I wanted to acknowledge that the season was up. One of my last relationships with a white person had been put to death by my need to fully show up and be fully seen and fully cared about in relationships. I was tired of prancing around my blackness to ensure his comfort. We do not have to think the same. But, if you feel your thoughts are superior to mine, in a world that values you as a white man, exceedingly, abundantly more than it values me as a black woman, then I am no longer interested in hearing your thoughts and you do not deserve my grace.

_________________________________________________________

A native of Nashville, TN, Yvette J. Green has lived in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C. for the last 20 years. Two sons make her a proud mother. She completed her BA at Xavier University of Louisiana and MA in English at UMCP. She has had a short memoir published in the Seasons of Our Lives-Winter: Stories from WomensMemoirs.com. Her first poems have been published in 45th Parallel Magazine, Indolent Books: What Rough Beast, Infection House, The Mark Literary Review and a hybrid essay/poem in The Critical Read and more work is forthcoming.

Twitter and IG: yvettemuses